To view the original article, please click here.

Although the rash of new rules and regulations instituted by China’s government on some of its largest tech markets and companies have caught the attention of many in the industry, those in the investment world say not to expect money to be pulled out of the second-largest economy in the world.

“Right now, on the new investment side, it’s business as usual,” said a venture capitalist who asked not to be named, but whose firm invests in China and has fewer than a dozen investments in the country.

“We talk to our legal and banking friends every week, but right now it’s business as usual for us,” the VC said.

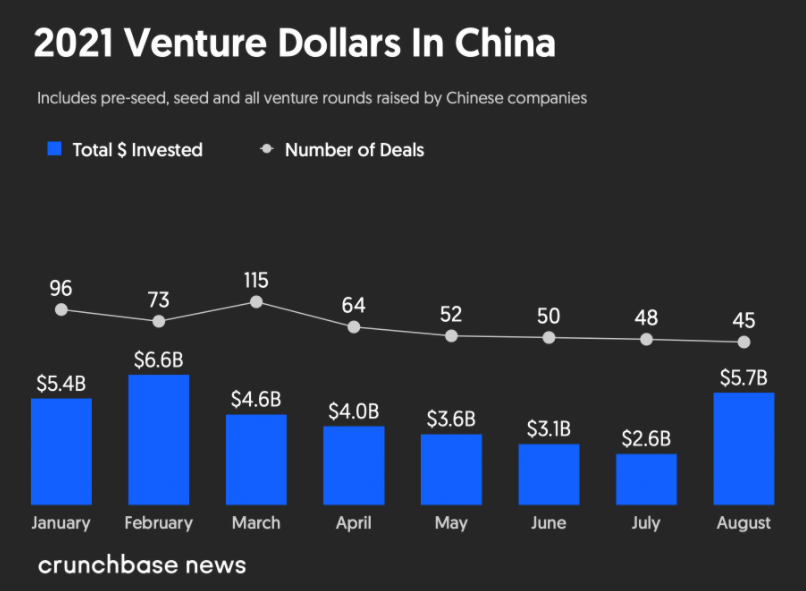

That business seems pretty robust this year, according to Crunchbase data. Already this year, companies in China have seen about $35.6 billion in venture capital invested—already surpassing last year’s total of about $29.1 billion.

Even in the last few months, when new regulations in China grabbed headlines–especially after the government announced it was investigating recently listed Didi on suspicion it had violated data privacy and national security laws in early July—venture capitalists seem high on the market, with August seeing $5.7 billion in venture capital flow into the country’s companies, the second-best month so far this year.

Too big to fail

For the two-month period after the Didi IPO, U.S. investors, for instance, still participated in 24 funding deals worth approximately $2.4 billion in China. While that represents a drop from 33 deals worth $2.9 billion for the same period last year, it is still significant money.

A couple of the top rounds U.S. investors took part in in the last two months included two deals at $500 million or more:

- Invesco Private Capital and GL Ventures participating in Abogen Biosciences’ $700 million Series C last month; and

- Intel Capital’s participation in electric-vehicle developer Zeekr’s $500 million seed round, also in August.

Those who watch the market in China are not anticipating those venture dollars to dip anytime soon or scare away foreign investors.

“The U.S. and Chinese economies are the two biggest in the world,” said Drew Bernstein, co-chairman of Marcum BP, an Asian-focused audit and advisory firm with offices in China and throughout Asia. “Chinese companies are not just coming to the U.S. market—they are being brought here by U.S. investors.”

Bernstein said China-based companies with strong revenue growth, corporate governance and disruptive technology will continue to spark interest from VCs and other investors.

“In fact, the smaller unicorns and non-unicorns such as emerging growth companies have promising futures given their growth trajectories,” he said.

New regulations an old story

Anik Bose, general partner at venture firm BGV, is not surprised by what he sees in China right now. About two decades ago, he helped 3Com develop a presence in China by aiding in the growth of Asian networking company H3C—a joint venture between Huawei and 3Com—as well as managing its $250 million 3Com Ventures fund as a senior vice president.

He said while the new regulations—which include China banning for-profit companies in the edtech industry, taking a minority stake in internet tech company Bytedance, and both the U.S. and China adding significantly more scrutiny to companies looking to go public in the U.S. via the “variable interest entities” model used by companies such as Didi and Alibaba for overseas listings—have grabbed attention, investors have been watching China tighten regulations around its growing tech economy since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012.

“This really isn’t a new story,” Bose said. “The level of restrictions has expanded in the last several years leading to what we’ve seen now.”

Bose, whose firm invests in other parts of Asia but not China, said venture money should continue to come into China just because of its pure size, especially from investors with a long road map.

“I think for those that look at China as a long-term play, it probably doesn’t change that much,” he said.

Looking elsewhere?

However, Bose does not dismiss the possibility of some investors looking at Southeast Asia, as well as India, which has become “much more competitive” concerning venture capital, he said.

While emerging growth companies between $500 million and $1 billion in value will remain attractive to venture investors when compared to some of their larger competitors due to their high-revenue growth trajectory and limited impact on China’s “Made in China” 2025 plan—an initiative to technologically upgrade manufacturing facilities—investors also will look elsewhere for those same types of companies, Bernstein added.

“Investors are searching far and wide for these opportunities, many of which can be found in Southeast Asia—the next frontier,” Bernstein said.

When all is said and done, those who invest in China believe access to the U.S. and its capital will trump all despite the new spat of regulations.

“At the end of the day, China will want access to the global equity markets,” said the unnamed venture investor, who added that the current uncertainty around regulations may hang over investors for six to 18 months, but it is unlikely to have a lasting impact on the second-biggest venture market in the world.

“I don’t think this is a heart attack,” said the investor. “It’s more of a bad cold.”