We can already detect fires from space, soon after they start. Here’s why we don’t yet have a nationwide system for alerting us when they do—but could someday.

For original article, click here.

Soon after the fire that would devastate Lahaina, Hawaii, sparked on the afternoon of Aug. 8, a U.S. government satellite 22,000 miles above the earth detected its ferocious heat.

That satellite is one of a pair belonging to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration that also allow U.S. agencies to track hurricanes.

Someday, such space-based tools could be a key part of methods for rapid detection of fires across the entire U.S.

For now, the U.S. government doesn’t have a robust capability to alert local authorities to such incidents. But various agencies, along with private companies, are working on it. Prototype systems have already rolled out, including NOAA’s own Next Generation Fire System.

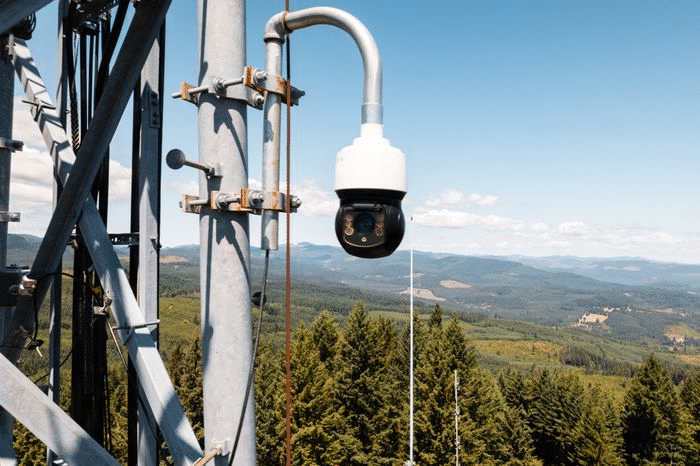

Indeed, a wide array of new technologies are being tested and deployed that can alert authorities minutes after a fire starts. These include tower-mounted cameras that use artificial intelligence to identify smoke, and sensors that are installed just above the forest floor, sniffing out fires using a kind of electronic nose.

“I can envision a day when your rural fire department might want to keep an eye on the next-generation fire system, or its successor,” says Scott Lindstrom, a wildfire expert at University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The instrument on the satellite that automatically detected the Lahaina fire is so sensitive that it can sometimes detect when a single house catches fire.

We only know about its success in detecting the fire on Maui because Chris Schmidt, a researcher at the Space Science and Engineering Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, analyzed the data it produced and gave a presentation on it.

Other new technologies allow fire agencies to determine what areas are at risk, and can help forest managers take steps to reduce the severity of future fires in those areas.

Collectively, these fire-prevention and fire-detection systems have the potential to be stitched into comprehensive “fire intelligence networks.” Already, early versions of these networks are rapidly informing the actions of firefighters. In the future, they might generate alerts that help us all cope with wildfires.

“I don’t think there is a silver-bullet solution to wildfires,” says Carsten Brinkschulte, chief executive of Dryad, a Berlin-based startup that makes tree-mounted sensors that can detect wildfires minutes after they’ve begun. “The problem is so big that we need to throw everything that we’ve got at the problem.”

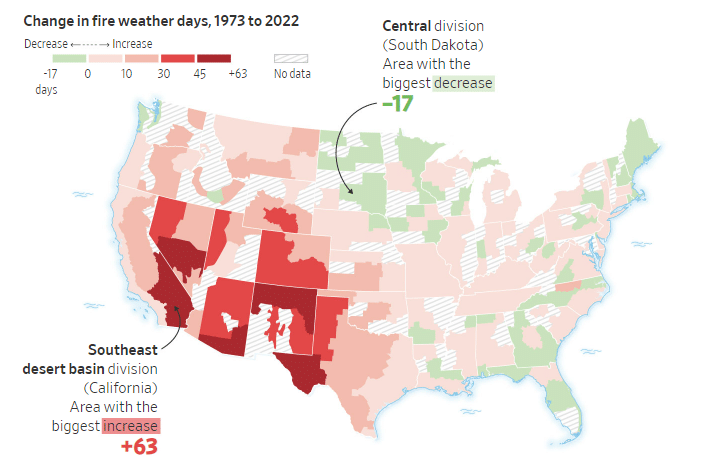

America is a tinderbox

The problem of wildfires in the U.S., especially in the West, is by some measures worse than at any other time in recorded history. Fires are bigger, hotter and more devastating, and the number of “megafires” that scorch more than 100,000 acres has increased sharply in the past decade.

Hotter, Drier, More Deadly: Fire Season in America’s West

Higher winds and temperatures, lower moisture, more fuel and more homes in harm’s way are making wildfires bigger and more dangerous than ever

Source: Climate Central

Camille Bressange/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

There’s evidence that early detection of fires is one of the most cost effective ways to tackle the problem of dangerous wildfires, says Matt Weiner, CEO of Megafire Action, a nonprofit founded to enact policy solutions to the megafire crisis.

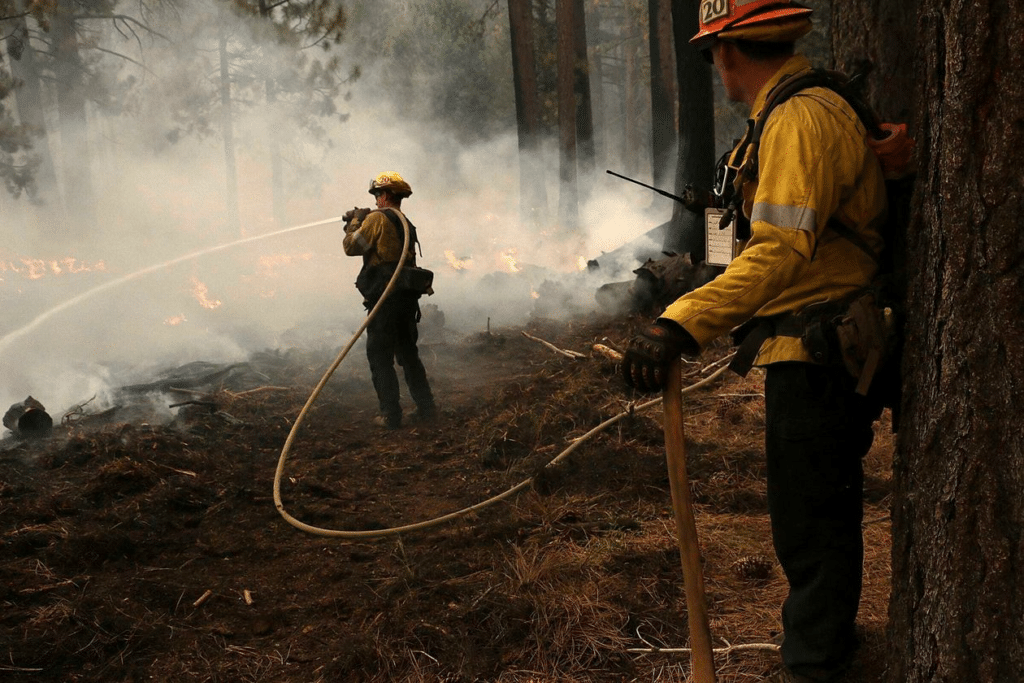

To prevent future devastating fires, technology must be used in service of what we already know about managing landscapes to save lives and property: We need more fire, not less, but it has to be the right kind—what Weiner and others call “good fire.”

Separating good fire from bad

“We have to do something drastically different in the next 10 years, or we’re going to lose it all,” says Eli Ilano, forest supervisor for Tahoe National Forest in California.

The system Ilano is using, called Land Tender, is made by a startup called Vibrant Planet. It’s one of a range of companies aiming to fight fires with data.

Land Tender creates maps of all the vegetation in an area, and its systems help forest supervisors and local communities figure out how to reduce their risk of catastrophic fire—in the most economical way. That means prescribed burns, which are fires deliberately started during the wet season, reduce the amount of fuel available to future fires, and mechanical thinning, which is just what it sounds like—removing trees and vegetation without clear-cutting an area, says Vibrant Planet CEO Allison Wolff.

Similarly, San Jose, Calif.-based AiDash is used by more than 80 utilities worldwide, to map and manage vegetation that may encroach on power lines, increasing the odds of outages and powerline-sparked fires, says CEO Abhishek Singh.

Pitfalls, opportunities in early detection

Other startups offer technology that can make up for shortcomings of satellite-based systems, which have limitations due to the great altitudes where they operate.

Cameras from Pano AI, mounted on cell towers, water tanks and other high points, can continuously scan in a circle 10 miles out, says CEO Sonia Kastner. Images from the cameras are uploaded through cellular networks or internet connection and checked by software that can identify smoke. Once a human verifies that it’s a fire, an alert is dispatched, via email and text, to customers including fire agencies. Many other companies offer competing camera-based technologies.

For the most at-risk areas with the highest value, there are now options for detecting fires almost as soon as they start. One is Dryad Networks’ solar-powered sensors, which can detect hydrogen, carbon monoxide and other gases, and use built-in artificial intelligence to evaluate when their levels change in a way that indicates a fire has started nearby.

To communicate with authorities, Dryad Networks’ sensors create a mesh network—like the ones now popular for spreading WiFi access across a home. But they use a different wireless protocol, called LoRa, which is good for low-power communication across long distances, and even as far as outer space.

Currently, the system is being tested in 50 different installations around the world, including one in a forest of redwoods by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

A future of firefighting robots and universal detection

At least one company has proposed automatically dispatching drones to dump water on fires soon after they’re detected, and others are trying variations on this idea.

But fighting fires remains a mostly low-tech affair. And all of the tech that can help with prevention and detection won’t touch political hurdles to funding and staffing firefighting efforts.

Implementing the kind of continent-spanning alert system that could underlie future firefighting efforts would require more advanced satellites than the ones currently flying. On the ground, we would also need all the data-processing and communication infrastructure needed to get the right alerts to the right people, as quickly as possible.

It would be very hard to create such a system, says Schmidt, the researcher who analyzed the satellite data from the Lahaina fire. “With the caveat that I’m speaking for myself and not my employer, I absolutely believe we could build something like that,” he adds. “It’s just a question of whether or not we want to prioritize it.”

Write to Christopher Mims at christopher.mims@wsj.com